While we have slowly moved into a post-pandemic Covid-19 phase, it is time to reflect on how the pandemic impacted us personally and professionally. As a global health researcher, it has been, ironically, good times from an academic productivity perspective. The pandemic triggered demand for policy advise and invitations to submit manuscripts by several journals, and allowed for the fast-pace generation of funding, studies and articles. Still, three years after the onset of the pandemic, I have mixed feelings about the entire period. Complementary to the social and public health impact, there have been other negative externalities, including the pressure to get manuscripts out, the overload of papers published on Covid-19 (with a varying degree of relevance) and the increasing difficulty to find scientists willing to peer-review a submitted academic manuscript. I have grown dissatisfied, tired and frustrated about this academic publication ‘machine’ that we have entrusted to make knowledge and learning available to a wider audience.

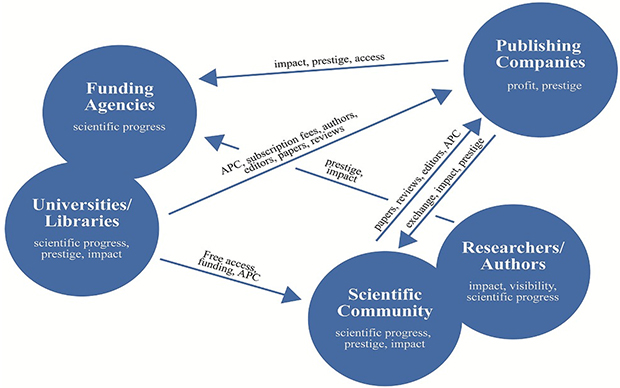

An online dialogue held with Collective members in October 2022 confirmed similar sentiments. Academic publishing has transformed considerably in the digital era. Before, this was organised by professional and academic associations that published journals against a membership fee. However, the demand for high-quality products and standardised processes have led many journals to outsource this function to commercial publishing houses such as Wiley, Elsevier and Springer, which have created a highly profitable market, including the use of paywalls.

Over the years, with the need for science to be accessible, the model of open-access journals has become in vogue. This is where the actual problem comes in – the article processing charge set by high-ranked journals can be over 2000 euros or more for research articles. These are hefty charges for authors without institutional support. Ironically, the publishing company makes about 30-40 % in profits per year, while extracting resources and time (e.g., in the form of peer-review) from often publicly funded research and researchers. The irony is that the research community is both producer and consumer of this ‘commodity’. It is understandable that some researchers have stopped writing and reviewing for commercial journals.

This mode of production is not only capitalist, but in essence also colonial. The system directs attention towards valuing Western scientific knowledge over other forms of knowledge, which leads to researchers over the whole world wanting to address questions that the West wants to be answered or finds impressive. This neglects the need for local, contextualised journals and for decentralized academic publishing infrastructure.

The incentive structure that makes this present rentier model possible is not only the publishing industry as such, but also the academic enterprise as it stands today. The fact that academic promotions are tied to journal publishing and journal impact factors is highly problematic. The big publishing companies have captured, and created vertical integration throughout, the different services required in the research cycle. Academic institutes have allowed themselves de facto to become dependent on this business model. Another problem is the behaviour of academics themselves. They don’t bother to read or refer to other sources that are not in English or not published in international journals. Many of them actively participate in keeping this incentive structure intact by allowing this hierarchical order of funding, publication, metrics, and evaluation to define their academic career.

During the Collective dialogue several alternative publishing models and approaches were mentioned. These include:

- Plan-S, an international consortium that demands that research funded by public grants must be published in compliant Open Access journals

- The Declaration on Research Assessment, which aims to provide a more comprehensive approach to research evaluation

- The ScieLo platform and journals, which originate from Latin-America and are a low-cost, publicly funded model supported by several research institutes across the continent.

While promoting open access, these initiatives do not resolve the market model that dominates journal publishing, but place more emphasis on affordable publishing costs covered by research funders. We need to ask ourselves: Why do we need to publish our scientific work in the first place? Is our research always relevant? If so, who is our target audience? And would there be other appropriate ways to share this knowledge publicly? Reflecting on these questions may lead us to publish in lower indexed and free or affordable outlets, or more localised but trustworthy journals; and to pay attention to a diversification of other, decolonised ways of exchanging scientific knowledge. This could be via podcasts, online seminar series or via newer media forms that the digital era allows. Doing so also requires a shift in mindset away from the academic hierarchic model and its incentive system defined by narrow metrics.

Perhaps the best way forward is to start with small steps. Together with colleagues and students, we can identify, and start publishing in, reliable open-source and publicly funded journals. Another step could be to pre-publish research as working papers, not necessarily via the privately funded pre-publishing servers but directly in a repository of one’s institution or that of a national research council. If enough researchers recognise the legitimacy of these alternative forms of publication and knowledge sharing, we are one step closer to ensuring that scientific knowledge is a global common good that is shared in a responsible manner.

This blog has been written after a discussion between, and dialogue facilitated by, the author and three other members of the Collective; Ronald Labonté, Seye Abimbola and Sakiko Fukuda-Parr. All of them have (associate) editorial positions in academic journals. For comments and suggestions please reach the author via Remco.van.de.pas@cphp-berlin.de