The COVID-19 pandemic has provided us with a stark opportunity to rethink business as usual. The pandemic experience has revealed some deep pathologies of 21st century capitalism that have catastrophic consequences for health. COVID-19 is just the most recent pandemic; many more are on the horizon and pandemic preparedness must be a policy priority. Looking at the system from 30,000 feet offers opportunities to identify structural misalignments, as well as low-hanging fruit ripe for regulatory targeting and reform.

Some of the features of contemporary capitalism that the pandemic laid bare include monopoly dominance of intellectual property owners (patents, trademark, and copyright), labour precarity (especially among “essential” workers) and structural racism. The risk-reward ratio is badly out of balance; those who face the highest risks are not those who obtain the highest reward. The concentration of private economic and political power has jeopardised the fulfillment of public purpose and made a mockery of bromides such as “no one is safe until everyone is safe” and “we are all in this together”.

The politics of patent protection is the politics of exclusion – excluding others from using the patented technology. Exclusion prevents competition, introduces scarcity, and concentrates rewards. The expansion of intellectual property protection under the World Trade Organization (WTO) reduced access to pandemic essentials including vaccines, personal protective equipment, therapeutics, diagnostics, and medical devices such as ventilators. Vaccine producers benefited from massive infusions of public funding, research, and advanced purchase guarantees; they amassed enormous profits. While taxpayers in rich countries effectively “de-risked” private sector investment, “vaccine billionaires” arose and many people in the Global South died waiting for doses. Owners of intellectual property doubled down on exclusion in the midst of a catastrophic pandemic by blocking even a narrow, limited, temporary waiver on intellectual property rights for pandemic essentials at the WTO.

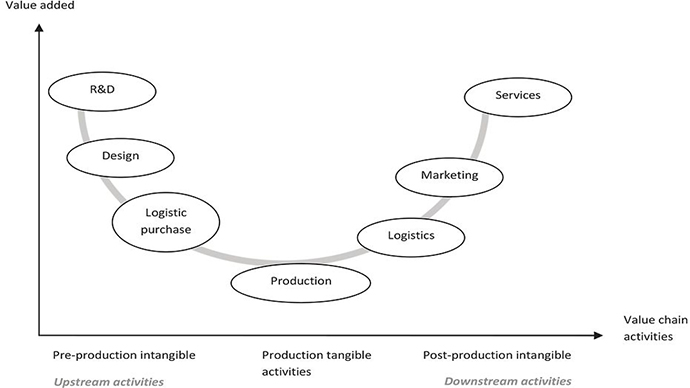

The "Smiling Curve" depicted below highlights the concentration of “value added” for owners of intangibles, now rendered as intellectual property at both ends of the smile. On the upper left side is “innovation” (e.g., patent and trade-secret-protected information/knowledge), and on the upper right side, “brand” (e.g., trademark). Notably, at the very bottom of the smiling curve is “production” – in other words, labour. This smiling curve was much flatter in the 1970s and 1980s but has radically steepened in recent years. Owners of intangibles have amassed astonishing wealth while labour has lost significant ground in terms of wages and social protection. Labour has travelled far deeper down the smiling curve. COVID-19 vividly demonstrated this dynamic by creating “vaccine billionaires” and relegating “essential workers” to the highest risk of death in a pandemic.

So-called “essential workers” included first-responders, medical personnel, aged-care workers, grocery stockers, bus drivers, teachers, agricultural and meat packing plant workers. These workers provided first-aid, life-saving interventions, transportation, food, and dedicated care for many of our loved ones. Many of these workers lacked paid sick leave, lived in cramped housing, and lacked essential protections from disease. As essential as they are, in fact, they were treated as disposable and suffered disproportionate exposure to disease and death. Poverty and precarity became powerful vectors of both.

So, how can we address the macro and micro pathologies of 21st century capitalism? What is the low-hanging fruit ripe for regulation? Relaxation of intellectual property rights for pandemic essentials and a new enforceable requirement for the transfer of know-how to produce vaccines would be a great start. Throughout COVID-19, governments across the OECD exercised “march-in” rights and implemented a range of “access-related” policies to protect their populations. And yet, they blocked these measures when the Global South asked to implement them. Today, WHO member states are starting to negotiate a Pandemic Treaty. As opposed to the WTO TRIPS waiver negotiations, these negotiations provide opportunities for a broader mandate and more possibilities for constructive trade-offs. As for the micro level pathologies exemplified by essential labour precarity – living wages, paid sick leave, and health insurance would be a good start.