Through Pangani Falls and Little Kihansi, the project takes an in-depth look at the evolution of Tanzanian-Norwegian energy cooperation from the late 1980s through the 1990s. With a heavy discursive and rhetorical focus, the project will analyze how “constellations of influence” – rapidly evolving agglomerations of state, corporate, and civil society actors – shaped the three energy projects discussed above. Based on extensive archival research, the project will tackle issues ranging from environmental concerns to donor-recipient power dynamics.

Consulted Archives:

- Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad)

- Royal Norwegian Embassy in Dar es Salaam

- Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE)

- Norwegian National Library’s Newspaper Collection

Duration

2020-2024

Financing

- Centre for Development and the Environment, UiO

- Nordic Civil Societies, UiO

- UiO:Norden

As the 1980s ended, Tanzania found itself in the midst of an energy crisis. Economic and population growth had put Tanzania’s aging energy infrastructure under increasing strain. It was clear that Tanzania needed to increase its production capacity, quickly. Hydropower sites across the country were evaluated, and Tanzanian officials picked what would become known as the Pangani Falls Redevelopment Project. Norway (Norad), Finland (Finnida), and Sweden (Sida) joined to finance the project. After discussion between the three Nordic donors, Norway was chosen as the lead donor. This meant that Norway would be responsible for the project’s administration, including communication with Tanzanian officials. MORE SUMMARY

Three overarching themes stand at the center of the project: Nordic cooperation, water management, and infrastructure and effect mitigation.

Nordic cooperation around the project was by no means problem free. Sweden and Finland considered pulling out of the project at different times. The difficult economic situation in the Nordics during the early 1990s made financing more challenging than expected. Time-consuming approval processes in the Nordics further delayed the project, worrying Tanzanian officials – any delay would cost Tanzania significant sums of money. Further delays were risked when one of the Swedish contractors engaged in the project went bankrupt, resulting in a debate over how the Swedish share of contracts could be preserved, if at all.

As the lead donor, Norway and Norad were put in between Tanzanian officials on the one side and Finland and Sweden on the other. This project will look at how Norway navigated this role to better understand the Tanzanian-Norwegian relationship.

No issue defined the project more than water management. Early on in the project, the donors understood that the water management office established in connection with the project, the Pangani Basin Water Office (PBWO), was struggling to establish itself. Tanzania was responsible for funding the office, however, the office was only receiving a fraction of promised funds. The situation took a critical turn when it became clear that there was less water in the Pangani river than previously estimated, due to drought and that agricultural interests were using more water expected.

A conflict on different fronts emerged. The first was between the donors and Tanzanian authorities over the funding of PBWO – a conflict that gives extensive insight into power dynamics in aid relationships. The second was on the ground in the project area. The imposition of water fees by PBWO met resistance from local agricultural interests and was criticized in Norway by environmental organizations and in newspapers such as Klassekampen. This conflict highlights how different actors interpreted the conflict to suit various narratives, as well as the challenges with implementing resource management programs in areas such as the Pangani Water Basin.

Lastly, efforts were made to improve local infrastructure and mitigate negative socioeconomic effects. Channeled largely through the PULIS program, these efforts struggled to gain traction and give a first-hand look at difficulties in establishing long-term cooperative agreements between various institutions and civil society groups that can ensure continued economic viability for infrastructure and effect mitigation efforts connected to energy projects.

Pangani would not be enough alone to cover Tanzania’s growing energy deficit. Kihansi was another hydropower project evaluated in the late 1980s. It later became a part of the World Bank’s larger Power VI project, and in the early 1990s, Tanzanian officials got to work trying to attract the donors necessary to make the project happen.

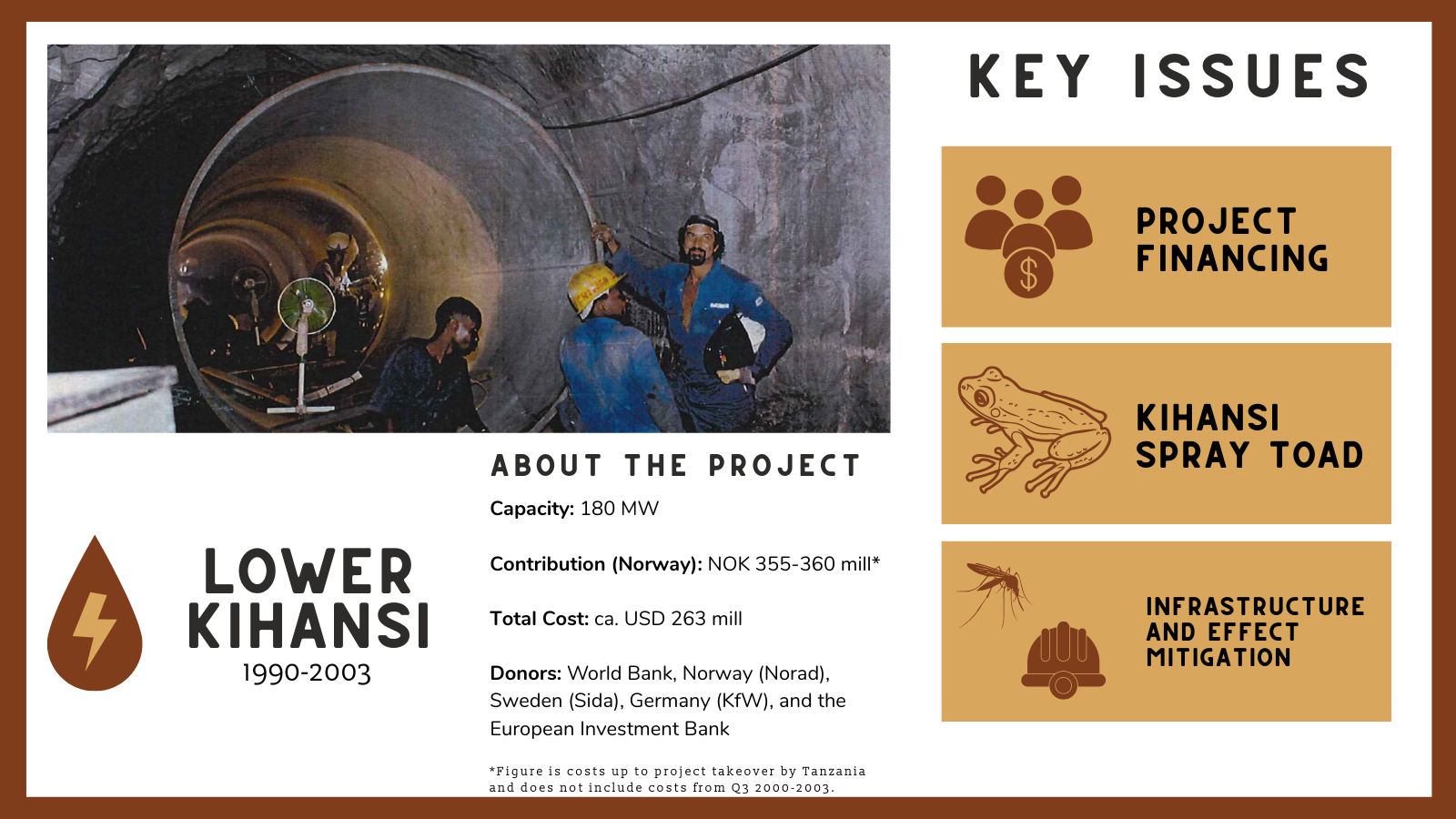

Three overarching themes stand at the center of the project: project financing, the Kihansi Spray Toad, and, as with Pangani, infrastructure and effect mitigation.

Project financing was indeed a core issue in the early stages of the project. It took several years for Tanzania to secure enough funding for a project in the early 1990s. Norway, in fact, would give support to the project, pull out of the project, and then rejoin the project – highlighting how challenging the financing environment was at the time. This project will take an in-depth look at the “financing dance” between Norway and Tanzania from 1990 to 1993 to generate a better understanding of the back and forth between both sides that eventually led Norway to rejoin the project in 1993 after leaving in 1992. It will also look into the role of giver conditionality in the context of environmental requirements Norway and Sweden set for their participation in the project.

One environmental issue, in particular, would come to define the project – the plight of the Kihansi Spray Toad. Through Norwegian-Swedish-financed environmental monitoring, the new toad species was discovered in 1996/7 in the area around and under Kihansi Falls. Further surveys argued the toad did not exist anywhere else in the world. This put the entire project in an extremely difficult predicament. The toad was dependent on mist from the falls for its survival. However, the project, as planned would significantly reduce this mist, putting the species in danger of survival. On the other hand, increasing the mist would mean sending more water past the power-generating turbines (minimum bypass flow), meaning less power generation and less income, putting the entire project economy of the project in danger and possibly causing significant danger to the Tanzanian economy.

How the Tanzanian-Norwegian energy relationship functioned in the context of this problem will be a central focus of the research on Kihansi. The issue of the Kihansi Spray Toad offers significant insight into questions around justice and sustainability in large energy projects such as Lower Kihansi, and how vary perspectives on these questions can affect the trajectory of a project.

In the end, the minimum bypass flow was not sufficiently increased, and the Kihansi Spray Toad went extinct in the wild. A Norwegian and Swedish-funded conservation effort saw several hundred toads shipped to U.S. zoos, where they still exist in captivity today.

Lastly, infrastructure and effect mitigation were again important themes. Norwegian officials and Tanzanian authorities sought to improve upon similar efforts done in connection to the Pangani project. Issues from the project-associated spread of malaria to resource management in local villages were tackled via largely Norwegian and Swedish-funded initiatives. These initiatives give valuable insight into cooperation with local civil society organizations and village councils, reflecting how various stakeholders interpreted and sought to respond to issues as they arose.